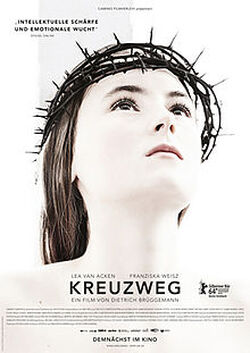

Film ReviewsStations Of The Cross: the devil's in the details

Apr 2 , 2015 Anchorage Press

|

|

Seven sacraments, 12 disciples, 14 Stations of the Cross, and one Christ define Maria's life and understanding of herself in the world. German filmmaker Dietrich Brüggemann's Stations of the Cross follows Maria's spiritual and physical journey paralleling Jesus' Stations of the Cross, from sentencing to crucifixion. Lea van Acken as Maria delivers a convincing performance, portraying an awkward teenager with a sense of destiny propelled by faith. Brüggemann's Stations of the Cross is a quiet film, deep in content and profoundly critical of the Catholic Church's culture of repression that misguides young minds by limiting their senses and curtailing their experiences. The film is also very complex. Viewers must take in detail upon detail that are filled with symbolism, history, and foretell Maria's fate, such as the color purple worn by different characters throughout the film. The liturgical symbolism of the color helps further the parallel between Maria's experience and Christ's journey to the cross.

Stations of the Cross takes place in modern day Germany so there are elements that come into play that further complicate the landscape. The film opens with a catechism class led by Father Weber (Florian Stetter who also starred in Beloved Sisters). Maria is a smart teenager, eager to please and up for providing all the right answers to Father Weber's questions. The first scene solidifies the building blocks for Maria's indoctrination into a rigidly moral and spiritual path just prior to her confirmation. The lessons, delivered with fervor, illustrate a disconnect between the Catholic Church and contemporary life, citing the perceived detrimental effects of Vatican II in the 1960s, which attempted to renew Catholic doctrine in a modern timeline and make it more accessible to the masses. The lesson goes on to position the young students as warriors in a quiet, but apparently ubiquitous spiritual war; as it turns out, the guidance they are given is about fighting temptation and sacrificing what some people would consider cultural elements that inform development. Things like self-discovery, music, clothing, teen magazines, cake and pretty dresses. Defining sin and sinful things to this degree creates confusion in the magnitude of actions. When Maria goes to confession all she can come up with is a laundry list of banal and innocent acts; it's as if the priest has to fish, interject and project sinful intent to events just to have something to pardon.

As the film unfolds, intricacies of Maria's character are revealed through her family dynamics. There is a key scene in which Maria and her mother are driving that reveals the culture of fear and intolerance permeating her family life. The mother (Franziska Weisz) is a stern character who turns on a dime, is judgmental, and whose fear of jazz and gospel reveals underlying racism likely a result of her inexperience. Inadvertently, the mother has put Maria on the same path but their sensibilities are very different so they yield different results. Maria's focus is on helping her baby brother who appears to have autistic or developmental conditions and at the age of four he has yet to be able to speak.

Maria is a loving person, and like her heroine, the venerable Anne de Guigné who lived in the early 1900s, she is the oldest of four and determined to sacrifice her life for Christ. This parallel is important to the timeline of the story because it's almost as if Maria's anorexia and downward spiral is designed to mimic the life of de Guigné. Maria's love for the Christian God brings to mind another young woman in the Church, Joan of Arc. A juxtaposition of this film with Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1927 masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc, shows a completely different threshold for sacrifice and awareness. The different styles of filmmaking help establish the circumstances in which Joan and Maria's characters coincide and differ. While Joan of Arc is fighting for God, against the Church; Maria is fighting for God through the Church. What is similar in both films is the un-Christ-like behavior of the Church. In the case of Dreyer's film, he used transcripts from Joan of Arc's trial to show the tyranny of the men in holy robes, while Brüggemann shows the absence of care and irresponsibility of the Church to its young warriors. Stations of the Cross reminds viewers of how impressionable young people are, and how adults around them can hide behind doctrine to absolve themselves from taking responsibility for their actions, or lack thereof.

Stations of the Cross plays at Bear Tooth Theatrepub on Monday, April 6 at 5:30 p.m.

Stations of the Cross takes place in modern day Germany so there are elements that come into play that further complicate the landscape. The film opens with a catechism class led by Father Weber (Florian Stetter who also starred in Beloved Sisters). Maria is a smart teenager, eager to please and up for providing all the right answers to Father Weber's questions. The first scene solidifies the building blocks for Maria's indoctrination into a rigidly moral and spiritual path just prior to her confirmation. The lessons, delivered with fervor, illustrate a disconnect between the Catholic Church and contemporary life, citing the perceived detrimental effects of Vatican II in the 1960s, which attempted to renew Catholic doctrine in a modern timeline and make it more accessible to the masses. The lesson goes on to position the young students as warriors in a quiet, but apparently ubiquitous spiritual war; as it turns out, the guidance they are given is about fighting temptation and sacrificing what some people would consider cultural elements that inform development. Things like self-discovery, music, clothing, teen magazines, cake and pretty dresses. Defining sin and sinful things to this degree creates confusion in the magnitude of actions. When Maria goes to confession all she can come up with is a laundry list of banal and innocent acts; it's as if the priest has to fish, interject and project sinful intent to events just to have something to pardon.

As the film unfolds, intricacies of Maria's character are revealed through her family dynamics. There is a key scene in which Maria and her mother are driving that reveals the culture of fear and intolerance permeating her family life. The mother (Franziska Weisz) is a stern character who turns on a dime, is judgmental, and whose fear of jazz and gospel reveals underlying racism likely a result of her inexperience. Inadvertently, the mother has put Maria on the same path but their sensibilities are very different so they yield different results. Maria's focus is on helping her baby brother who appears to have autistic or developmental conditions and at the age of four he has yet to be able to speak.

Maria is a loving person, and like her heroine, the venerable Anne de Guigné who lived in the early 1900s, she is the oldest of four and determined to sacrifice her life for Christ. This parallel is important to the timeline of the story because it's almost as if Maria's anorexia and downward spiral is designed to mimic the life of de Guigné. Maria's love for the Christian God brings to mind another young woman in the Church, Joan of Arc. A juxtaposition of this film with Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1927 masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc, shows a completely different threshold for sacrifice and awareness. The different styles of filmmaking help establish the circumstances in which Joan and Maria's characters coincide and differ. While Joan of Arc is fighting for God, against the Church; Maria is fighting for God through the Church. What is similar in both films is the un-Christ-like behavior of the Church. In the case of Dreyer's film, he used transcripts from Joan of Arc's trial to show the tyranny of the men in holy robes, while Brüggemann shows the absence of care and irresponsibility of the Church to its young warriors. Stations of the Cross reminds viewers of how impressionable young people are, and how adults around them can hide behind doctrine to absolve themselves from taking responsibility for their actions, or lack thereof.

Stations of the Cross plays at Bear Tooth Theatrepub on Monday, April 6 at 5:30 p.m.