|

Apr 14, 2016 Anchorage Press

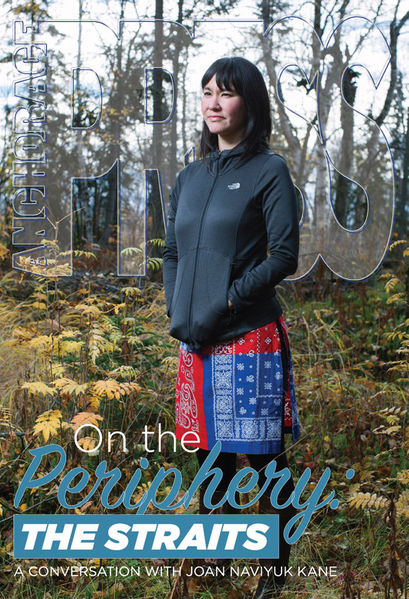

On the Periphery: The Straits, A conversation with Joan Naviyuk KaneI overslept, as I usually do when I get home at four in the morning and have to be up at 8 a.m. the same day. I jumped out of bed especially motivated because Joan Naviyuk Kane was coming over for breakfast at 10. The fridge was stocked but time was flying so I consulted The New James Beard Cookbook from the 1980s. I flipped through it and quickly spotted his assortment of shirred eggs recipes. Today was special; Joan had made time to talk with me about her collection of poems, The Straits. The Straits is Volume IV, Number 2 in the Voices From American Land chapbook series, which was released on October 6, 2015. In addition to The Straits, Joan is also the author of The Cormorant Hunter's Wife, and Hyperboreal. She's received prestigious awards including the Whiting Writer's Award, and the Donald Hall Prize in Poetry, among others. Her fellowships include the Rasmuson Foundation, the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, the Hermitage Artist Retreat and many more. Joan graduated from Harvard College, where she was a Harvard National Scholar, and Columbia University's School of the Arts, where she was the recipient of a graduate Writing Fellowship. She is MFA faculty at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. New work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Best American Poetry 2015, Poetry, Prairie Schooner, and South Magazine. Now, what to feed her?

I skipped over the cream-based recipes. Forget bland eggs, today was about olive oil, tomatoes, eggs, spices, condiments and copious spoonfuls of pesto arranged just so in white ramekins and baked just right. The eggs were accompanied by smoked salmon, manchego cheese, dense slices of toast, scones, coffee and juice; the table was set. I received the review copy of The Straits just 10 days before our breakfast meeting. I read it in my usual way, in bits here and there initially, over coffee, at the table, in the car; and cover-to-cover at the studio and in bed. I sat with the poems, and found myself coming back to them even when I wasn't reading them; they became a part of my own thoughts as I daydreamed along Turnagain Arm or lost myself in cloudscapes. Kane's language rings true, her words are deliberate and precise. She crafts a sustained tension throughout the body of the chapbook, showing deep emotional intelligence made accessible through a steadfast composure. The Straits is unique and universal at the same time, giving readers a sense of place. Whether experienced or imagined-the place exists-and is an otherness made of history and culture, personal experience and wonder. The space sits at a periphery that engenders creation, primal to all human beings and transcendental; "between the shadow and the soul" as Neruda writes. Kane's roots are on Ugiuvak or King Island, a small island in the Bering Sea, about 90 miles northwest of Nome. King Island is the traditional home of a population of Inuit people, and until 1959 it was the home of Joan Naviyuk Kane's family and ancestors. The Bureau of Indian Affairs closed the school and forcefully took the children to mainland Alaska, requiring elders and other community members to also relocate. By the 1970s, all King Islanders lived off the island. Kane was able to visit her mother's childhood home with a handful of people. The journey that took more than 26 hours aboard a 42-foot aluminum-hulled boat from Nome's small boat harbor-and several more hours in a small inflatable Zodiac dinghy between the boat anchored offshore and the island itself, is at the heart of The Straits. Conversations are effortless between Kane and me, especially about art and writing; the following are threads of our morning dialogue, shirred eggs and all. The Periphery [Anchorage Press]I've been to the Bering Sea a couple of times. I'm very lucky, it's beautiful. [Joan Kane]It is. There's that sublimity of the landscape, which is in some way this neo-romantic, post-enlightenment response. But most human beings are landlocked, most never leave home. The concept of space for me is well I was on St. Paul Island on a cliff overlooking the seals. You start thinking about where you are standing, geographically, and what's around it, and what's around that. You envision your place in the world at that particular moment and it's right "there", you're standing on the edge of "it." You're on the periphery. And it's mind-blowing. When I read The Straits, I found there's precision in the word choice. There's a reason for everything but it also feels like it's right "there," at that line. Right, right, I'm glad that comes through because I've been thinking about that, and thinking especially in the context of dealing with what it is to be a Native writer where you have essentially populist writers whose work can be-and they want it to be-the center of the mainstream. There's something about centrism, or populism, or populist rhetoric Or acceptance. Right, acceptance but also self-acceptance by fitting in, or not being on the margin or periphery. Or being validated. The reason poems have always interested me is because they're a way not to engage, or a way to disengage, a way to be, or not just be, in an image, or create an image, or represent an image. There's something else that doesn't quite fit in and doesn't quite you know it's kind of like, "who cares?" That is part of what has always been attractive to me; it's like a Morrissey song. Dialogue, intention, moving something forward, poems are always something outside of the typical narrative structures of plot, conflict, trauma. Poems can work outside the narrative burden. Language and writing Why don't you translate some of your poems into Iñupiaq? I'm a terrible translator. I'm very skeptical about my impulse to want to write in Iñupiaq because on the one hand, I don't have the language at my disposal, and I don't want to continue to perpetuate some idea that I really do because I think that's problematic and it gives some false appearance that I can do this. It's one thing to go into a meeting and speak enough Iñupiaq, and then at the same time not really speak enough so that it's a language that I use in my daily life in the same way. Then there's just the process of going to my mom or my relatives and saying, "Here's my poem " It's like in The Big Lebowski when the landlord has the dance and they go and are sort of like "Oh Jesus " That's kind of what it feels like. Another reason I don't translate some of them is because it's almost a generative thing. I think, too, there's the Gayatri Spivak notion of what is untranslatable, and the process of translation. English is a colonizing, steamrolling language that wants to take everything in or seek equivalence. One of the things that creative writing students always want are writing prompts and writing exercises. But I find that through technology-especially coding, and this idea of homolinguistic translation-the exercises that are the most cognitively, and also in practice, generative, are those where there's a sort of infinite substitution at the same time that you're actually trying to produce an effect. In that space of digression or of moving away from having a pedantic end, is where I'm free to create art. That's where I'm free to move away from meaning, and get into not just sensibility, or emotion, or feeling, but into something "other." Language is just a tool and words are a material. This precision I'm always working out with poems is one of the reasons I haven't written a novel yet, because I find that to be maddening, in the context of prose. Part of my fan-girl crush on David Foster Wallace is that he was able to sustain that precision over thousands and thousands of pages. There is this sort of authority that's there, something I really like in a nerdy way. An authority, footnote or etymology that's there is something I really like, and it's something that partly comes from learning HTML, you realize there's a way to get things done. Language can be used as a procedural thing. Going back to the Romantic writers, they're not overtly precise. It's wonderful because they make the experience really enjoyable, and flowery and everything else to get to the main idea, and the main idea is always very precise. But it's like, "how pimped out is your car?" Yes, and part of the beauty of them is they are so pimped out that it's on the one hand distracting, but there is actually something going on there, something of substance and is not just in the sensual pleasure of language or image or sound. I've been reading Proust for 15 years now; I've been reading the same Proust for the last 15 years As we all have. I don't think I'll ever finish it. Which is amazing, to think of how he wrote it! That's the mystery always to me in seeing a book. I don't know how. Sometimes I have this feeling of "Oh my God! I wrote that I don't remember writing this," which is also the pleasure of being an artist. And it's not like a hedonistic, "Oh when I was in my 20s and I lived in New York " It wasn't done in a blackout but there's some loss of the self that happens in art, on the page. It's an extension of memory, and you don't remember everything, you remember certain things. There's this sort of American relationship to the past and understanding, I think of Proust and what is the key to your past? What is the key to the world outside of yourself? In some ways, another romantic sensibility of what are the interstitial points of connection? Writing a poem When you start writing, what is poetry, what is story, what is prose? Is it a deliberate choice to say "I'm going to write a poem"? Or is it something, a voice, a line, something that comes and then you follow it and it takes shape? That's the problem, it's something that comes and then I build everything around what has risen to the top, it has somehow broken through, and "this" is a poem, it's not a tweet, it's not something I say in ordinary language. There's a need for ordered speech or heightened speech, and meaning as well. I know a painting is going to work when there's something that I can say about it, not to the public, not like that, but I'll be painting and there will be a line, a sentence, a description, anything and the moment I can say that line to the painting, then I know the direction of the painting. I know what the painting is saying to me. It's something that just emerges and I don't know what comes first. There's a dialogue. What I'm trying to fit into this schematic is that there is something that is not just performance or portrayal, right? There's something that is transformative-not an act of translation because that implies equivalence or knowledge of all things or control over not just your technique but also whatever is going on beneath the surface, but there's something there in really creating art-not just producing a poem or making a painting, it's about when you're creating something. It's between utterance and visualizing the utterance. But when you talk about those "spaces," that's what I think of. And back to this notion of the periphery, there's something about the periphery; that is a reminder that there is something uniquely human about it, that kind of space where you might suspend your belief or your skepticism but also something very generative. Something that's there, right at the cusp of transitional space. There's something that is like a record. It's almost like a recovered memory. You didn't know it was there, it came up and then it went, but in that coming up and going you see it and it's enough to see it for a second, and that changes what comes next. Now there's research and a lot discussion about how as a mother, your DNA actually changes after you're pregnant. You retain traces of your children's unique DNA in your body. It's not just that you're changed because you were pregnant for nine months; no, you've had another living person inside of you and it changed you and not just in normative cultural ways. There's something that happens at a cellular level, at the level of life and creation. I don't know, it makes it sound too cheesy. No, no. it's not too cheesy at all. It makes sense both for the survival of the species, and also for this idea that at the end of the day we're all matter. Maybe this is a little too over-determined, but that the point of creating art is that it transforms these cognitions into matter in some way, whether or not you're an artist that produces a document, or a commodity or product; but that's how humans interact with the world, through relation to matter. Not just humans. "If only we all understood the importance and function of language; that not everything is a rant to put on Facebook, or not everything is this perpetual self-definition or connectivity." Everything. But that also limits human beings and then you have cultures of materialism where you care about what you can see and not about what you can't see. Three Poetry Books I've read your three books and there's definitely some sort of ... journey is a cheesy word, but I don't want to call it progression because it's not like that, but honing in, it seems like. I don't know if it's the honing in has to do with the language or the content. I think that some of it is the content. And one thing that also troubles me, particularly about my second book, Hyperboreal, and this chapbook is that I became focused on a type of performativity and identity that I don't think really serves what I want to do and why I'm drawn to, again, this peripheral notion of the self through language and through poem. The poems I like, like the Sylvia Plath poems, have very little to do with Plath the housewife and the mother. Poems I like about Plath are the ones where she says "The moon is not my mother," see "Her blacks crackle and drag." These have nothing to do with who she has to be for someone else. She touches the bottom with her toe, and that's what I'm drawn to, that gesture. I feel like in some ways, in Hyperboreal, I was trying to make something useful out of being a mom and an Eskimo. In other ways, I like the openness. Every poem in Hyperboreal is a first draft, that's how it came out. And, there's a lot to that! Yes, and that's why I value it. It's scary, but I'm also grateful and wonder if that will ever happen again, where something cracks open and I create. But then, in The Straits, I feel like I transition in the direction of performative roles of gender, and culture and normative identity; speaking to, or dealing with my own apprehensions of geography and also not wanting to be the "Alaskan poet." When I agreed to write The Straits, I thought it would be an end product for my trip to King Island but there is no end product for the trip. There is no point in which I say, "Yes, I got to go once, and I'd really like to go again." Once I found the real reason for wanting to go was not about playing into some myth of "Oh, look how assimilated I became and look how much I've regained because it's all right there and my past is accessible to me, and my family's past;" it's not like that, it's like "No! how much did we lose?" There's nothing I can do about that loss. If we really want to keep the place alive for another generation, and have kids born in the 21st century go back to King Island and have it mean what it did 50 years ago, we need to get beyond self-serving notions-the myth of America and upward mobility; we need to undo these tragic and real policy and practical matters. I'm worried about the chapbook in the sense that I don't know if there is a unified message. I feel like in the first book, The Cormorant Hunter's Wife, I had a clear sense of "I have access to a real set of knowledge and stories and a past, and I can create alongside or somehow in conversation with it." The second book was like "wow I can do this." And this one, I don't know. Sometimes there's value in that, sometimes it's a matter of perspective and distance. How has The Straits been received outside of Alaska? It hasn't. But I've been reading from it for years, that's the problem too, or the benefit of being a profesh poet. Even if people have to hear the same poem every six months, it's OK if the poem is good enough. But how it's received if people haven't been to the Arctic or Subarctic, or haven't been to Nome I don't know. The problem with having a predominantly non-Inupiaq audience is that it's easy to mistake my writing about place and about the land as something rhapsodic and sentimental as opposed to this other very real sense-which having been there you understand- that part of the power of the landscape is not about wild spaces but it's about, "Look how small I am in relation to the rest of the world." Selected Poem: "Our Distant Northern Sea" The title for "Our Distant Northern Sea" comes from Matt Arnold's poem, "Dover Beach." I was in Barrow in March of 2013 when Edward Itta was giving a lecture at I?isa?vik College, and part of his speech was that If only we learned the old ways, we'd learn how critical we are to each other. I first wrote "Our Distant Northern Sea" as a response to an invitation to contribute to a basketball and poverty issue in [the University of Nebraska's literary magazine] Prairie Schooner. Inuk hockey player Jordan Tootoo has a memoir called, All the Way: My Life on the Ice. He and his older brother were both brought up to be in the NHL feeder leagues in Canada. When he was 19 his brother ended up getting a DUI and he killed himself a couple of days later. When Jordan made it to the NHL he went off the rails and became an alcoholic. He had a quote that talked about when he was drinking, and he had gotten used to popularity and being the center of attention, and if there was something he couldn't work out when he was drinking, then he'd bring it out on the ice. And I was thinking, "On the ice does he mean on the sea ice?" Because he grew up in an Inuit village and so I was thinking about the sea ice. It's not just of metaphorical importance to me, it's very real. How amazing it has been in my life the times that I've been out on the ice, on that periphery and the inherent danger that it could break open at any second. There's the risk but also something really powerful, how this being out on the ice, the ice of performing and being in the white gaze in hockey. The first line, "What do you see out there on the ice?" it's not just metaphorical, it's the very real sea ice that allowed his ancestors and my ancestors to speak the same fucking language. Which is going away. Not just the language, but also the ice and the importance that we have as Inuit people to each other. It's not just about Eskimos being critical to other Eskimos, it's about people. If only we all understood the importance and function of language, that not everything is a rant to put on Facebook, or not everything is this perpetual self-definition or connectivity. If we only understood all these social problems, for Native people such as poverty, booze and suicide. But thinking about what a temporary position we've been in; for Inuit people for the last 50 or 100 years for Native people, or for New World or people of color for the last 500 or 600 years. |

"our distant northern sea" |